- Home

- >

- APU Articles

- >

- News Article

Traveling Through the Dark

January 15, 2025 | Category Humanities and Sciences | Written By Diana Pavlac Glyer

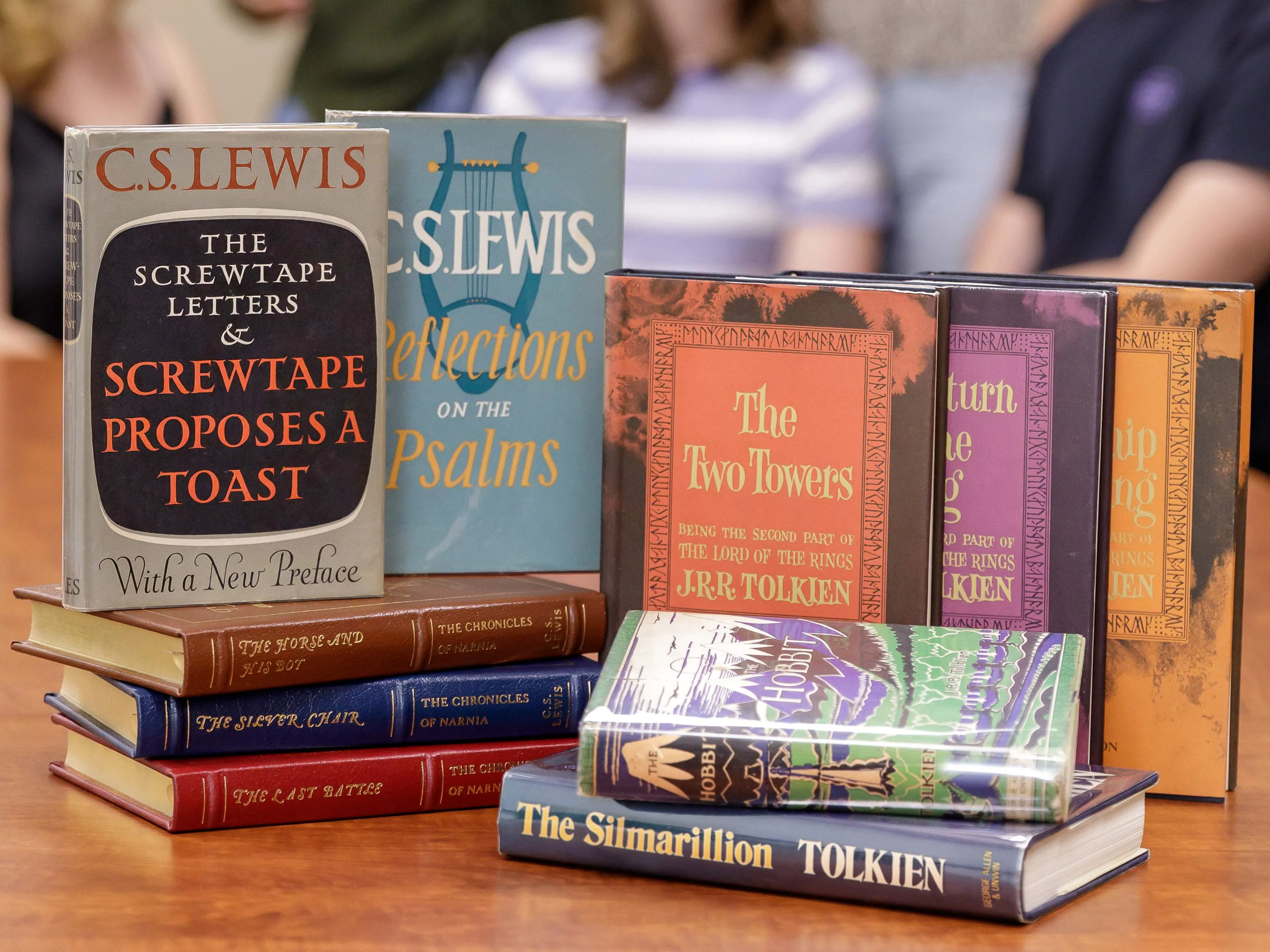

You may know that C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien were longtime friends. At the very end of Lewis’s life, when he became quite ill, Tolkien continued to visit him regularly. They spent hours together, reminiscing about their lives as college professors, their years of family vacations together, and the unexpected and far-ranging impact of their writing, including The Chronicles of Narnia, Mere Christianity, The Hobbit, and The Lord of the Rings.

When Lewis died in 1963, Tolkien wrote, “So far I have felt the normal feelings of a man my age — like an old tree that is losing all its leaves one by one: this feels like an axe-blow near the roots.”1

But earlier, in 1926 when they first met, it was a different story. From Tolkien’s point of view, there was nothing memorable about meeting Lewis. But Lewis definitely remembered meeting Tolkien. He described it in some detail, calling Tolkien “a pale, fluent fellow” who ”needs a smack.”2

It was a rough beginning! And after that? Well, after that, it got worse. They discovered that they stood on opposite sides of a bitter debate about curriculum. They started somewhat suspicious of one another and then became downright hostile.

And yet they ended their lives as friends.

How did they manage it? Things began to change when Tolkien started a book club and

invited Lewis to join. As this small group of faculty colleagues from different disciplines

spent time together,

they built trust. As Lewis says in The Four Loves, friendship develops as people spend time side by side, listening and learning. I

don’t mean to suggest that they “found common ground” or achieved some kind of consensus.

What changed? They discovered that deep affection can emerge when we seek first to

understand. Over time, Lewis and Tolkien discovered that their world was a bigger

world because they had each other in their lives.

It’s a lofty goal: to harness the wisdom that comes from a multitude of perspectives. It’s a lofty goal, and it is not easy. Remember: As a newly minted college teacher, Lewis thought the way forward was an insult and then a good smack.

So what about us? How do we remain open, curious, humble, and patient even as we acknowledge our differences? What guiding lights can help us find our way through challenging times?

It’s complicated, so I want to mention just four key ideas that helped Lewis and

Tolkien. In order to negotiate their differences, Lewis and Tolkien looked to the

past to find guiding principles for their future. They looked to philosophy and history,

literature and theology, to find guiding principles

to light their way.

The first principle is courage. You know the saying: Courage is not the absence of fear; it’s taking action despite our fear. The truth is we wouldn’t need courage if we were not afraid. I would take it a bit further: Being truly brave requires that we acknowledge our fears, daring to be honest about what is at stake.

It also seems clear that for the Christian, fear becomes the very thing that drives us to God. In other words, we find the courage to do what we are called to do as we look to the Source of all strength.

So our first guiding light is courage. And a second is moderation, or what is usually

called

temperance. As I struggle to understand temperance, the word “balance” is helpful: not too much

and not too little. Aristotle would have us all seek the “golden mean”—that is, the

appropriate balance point between excess and deficiency. Can I confess?

This one is hard for me. Balance. The balance between home and school, work and rest, structure and spontaneity: Every decision I face seems to be a battle between competing priorities. I spend a lot of time wrestling to find that balance point, to be guided by temperance. For me, it’s not easy.

But it does get easier for me as I grow in prudence, our third guiding light. I think the word prudence is an unfortunate word: these days, we think it means “timid” or “shy,” or perhaps being overly concerned with proper behavior.

The heart of prudence, though, is simply the practical application of wisdom to life’s

great challenges. Let me explain it this way: I think of knowledge as knowing what

is right, and wisdom is knowing how to do what is right. In other words, knowledge

and wisdom have to do with how we think. But prudence is combining wisdom with courage

and then actually making better choices. Josef Pieper explains that prudence is more

than contemplation. It is action that is built upon

knowledge, experience, and insight.3

But here’s the hard part: Prudence is right action, and the only way to learn it is by practice. As Pieper says, we grow in prudence by making choices repeatedly with goodness itself in mind. Perhaps you watched the recent Olympics in Paris. Stunning performances. Supernatural strength and grace! Those competitors start with amazing talent. But natural ability has been perfected by hour after hour after hour of practice.

Prudence is like that. It is perfected through practice. And here’s the thing: That

kind of goodness,

practiced year after year, becomes the training ground for our souls. Ultimately,

a commitment to prudence redefines the kind of people we become.

As Lewis and Tolkien learned to appreciate their differences, they grew in courage and in temperance and in prudence. And the fourth and final light that guided them is justice. We tend to think of justice as the big things: laws, policies, and systems. And rightly so. It is. It absolutely is. But it is also interesting to me that in The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien writes a story in which very ordinary people, Hobbit-sized heroes, overcome great evil by simply doing all they can despite the odds. Lewis explains: “Justice means much more than the sort of thing that goes on in law courts. [Justice] is the old name for everything we should now call ‘fairness’; it includes honesty, give and take, truthfulness, keeping promises, and all that side of life.”4

Justice. Along with courage, temperance, and prudence. Four simple ideas. Simple,

but not easy. Lewis writes about all four ideas, all four of these cardinal virtues,

in Mere Christianity. He calls them “directions for running the human machine”; he calls them guidelines

that “prevent a breakdown,

or a strain, or a friction.”5 Through his experiences in the trenches of the First World War, and through the hard

work of forging a friendship with J.R.R. Tolkien, Lewis came to believe that courage,

temperance, prudence, and justice provide the necessary instructions for how to appreciate

our differences, resolve our conflicts, make hard decisions, and grow in God-honoring

character.

In this season, my prayer is that our courage will never fail; that temperance will guard and guide us; that wisdom and prudence will serve as trustworthy companions; and that justice will light our path every step of the way.

May we be guided in all this by love. May hope attend us every step of the way. And one more: May we be grounded in faith: believing that in all these things, in courage, temperance, prudence, and justice, in faith, in hope, and in love, God is our constant companion, and He will guide our way.

I want to conclude with a quotation from E.L. Doctorow. He said that writing a novel is like “driving a car at night, you only see what the headlights light up, but you can make the whole trip that way.”6 Driving at night. Making our way through the dark. It’s true of the experience of writing a novel. And maybe it’s true for all of us. Most of the time, we feel like we are traveling through the dark, just trying to find our way.

As we face challenges and competing priorities, I suggest that all four of the classical

virtues taken together—courage, temperance, prudence, and justice—along with the theological

virtues of faith and hope and love, provide trustworthy guidance for all of us. Taken

together, they serve as guiding lights for the work God is calling us to do. So let’s

hold fast to courage, temperance, prudence, and

justice. And to faith, and hope, and love. We can make the whole trip that way.

1 Letter to his daughter, Priscilla Tolkien. 26 November 1963.

2 C.S. Lewis, All My Road Before Me, 393.

3 Pieper, The Four Cardinal Virtues.

4 Lewis, Mere Christianity, Book III, Chapter 2

⁵ Lewis, Mere Christianity, Book II, Chapter 1.

⁶ https://www.trolleyjournal.com/doctorow-kennedy