- Home

- >

- APU Articles

- >

- News Article

Restorative Justice in Schools: A San Bernardino Educational Leader Upholds Students’ Promise and Potential

July 14, 2020 | Written By Evelyn Allen, MS ’19

Related Links

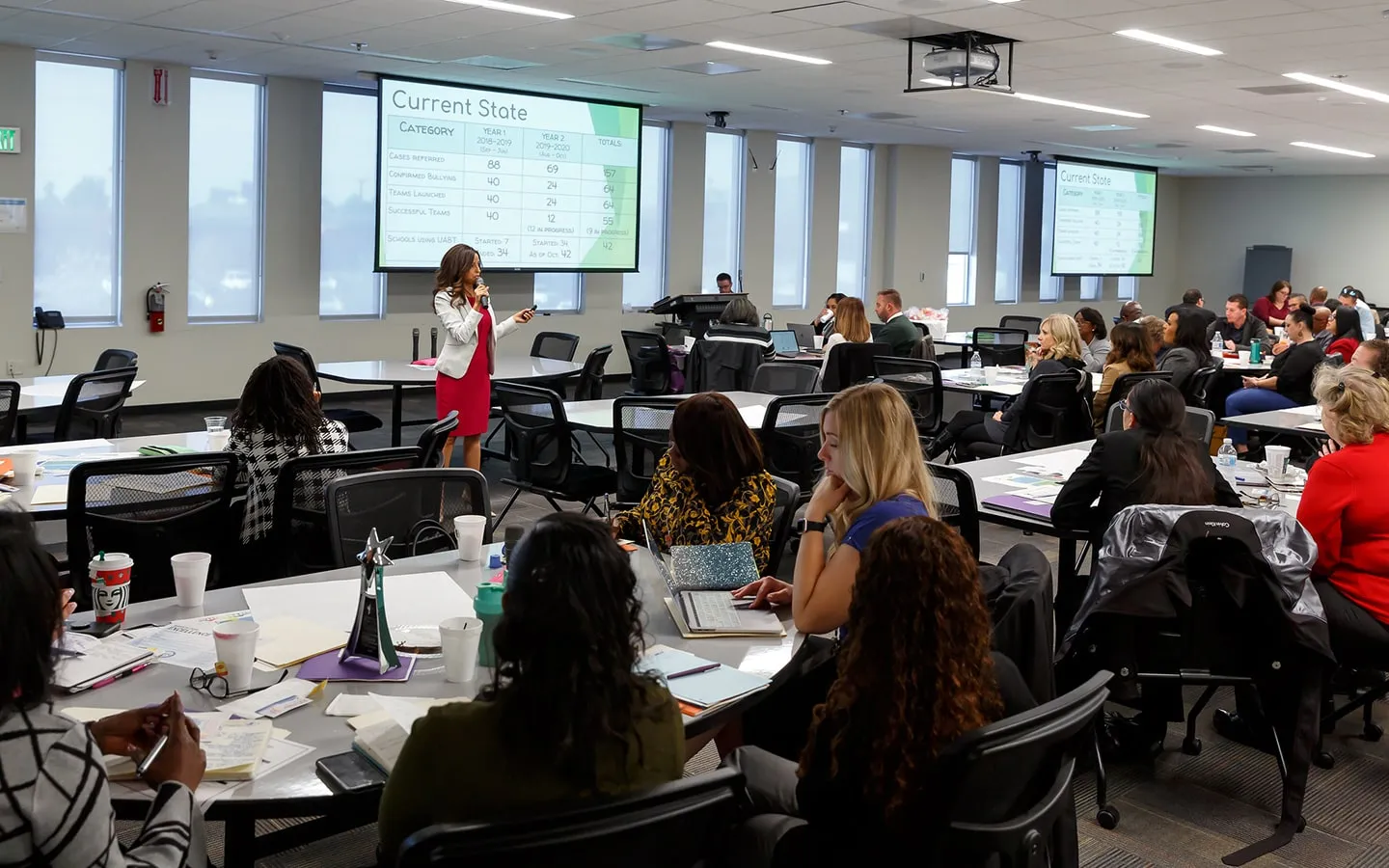

That’s why, when Marlene Bicondova, EdD ’19, presents data on her school district’s anti-bullying intervention, the significant results make virtually everyone take notice.

At a gathering of school leaders from across the San Bernardino City Unified School District (SBCUSD), Bicondova walked through the process and then let the numbers do the talking. Since

implementing the Bullying Intervention System (BIS), Bicondova’s team has addressed

102 confirmed cases of bullying. (Cases deemed to be non-bullying conflicts or behaviors

are addressed with appropriate interventions.) As of March 2020, before stay-at-home

orders, a total of 95 anti-bullying teams have been launched, with 78 teams achieving

a complete resolution of the problem. The other 17 teams remain in progress and will

continue when school is back in session. Notably, the method had a 100 percent success

rate in resolving all confirmed cases of bullying during the first year of implementation.

“Addressing bullying has been a huge district undertaking,” said Bicondova, the director of positive youth development for the district, one of California’s largest with more than 57,000 students. “Our approach involves a screening process that takes place within 24 hours of any reported situation. From there, we deploy our expert team to the school site, and they continue their work until the targeted student notes a total resolution. It has had such an incredible impact that we’re now training other districts on how to use this approach.”

With a career spanning 20 years in public education, Bicondova and her team address many of the most complex challenges facing SBCUSD students, including disciplinary actions and attendance issues. “I see the toughest kids at the toughest moments in their lives,” said Bicondova. “Most are coping with mental health issues and trauma, and they often need time and resources to get better.”

Not long ago, it would have been common to label students in this category “at risk.” But a movement among educators and Sacramento lawmakers led this year to swapping out the pejorative term for “at promise” and “at potential” in California’s education and penal codes. The reframing is an important step, said Bicondova. “Language matters. When you label students at risk, they tend to live out that label,” she said. “I strive to help students see themselves apart from their behaviors or their problems. No matter how bad the situation is, there’s always a counter story of redemption that they can choose.”

In pressure-filled situations, Bicondova returns time and again to the fundamental strategies first learned as a middle-school principal, especially restorative justice in schools, which is built on the premise that all community members are important. Practitioners minimize punitive measures—like suspension or expulsion—instead focusing on responsibility for offenders and restitution for victims.

Supporting the district’s justice-driven efforts, Bicondova’s doctoral dissertation in the School of Education’s EdD in Educational Leadership program centered on restorative practices. Her research revealed meaningful findings for teaching and learning, including the vital role school counselors play in restorative justice practices, said Randy Fall, PhD, professor in the Department of School Counseling and School Psychology who chaired Bicondova’s dissertation committee. “Districts will use these findings and resources to develop and apply these methods in the classroom, which will produce important outcomes, like fewer suspensions and expulsions, and more cohesive learning communities,” he said.

Such practices to redirect patterns of school discipline are significant and timely as educational systems grapple with issues of inequity, said Anita Henck, PhD, dean of the School of Education. “National data show that school discipline and suspension rates are disproportionately high for students of color,” said Henck. “The investment in restorative justice in schools has the potential to change the conversation and, ultimately, the outcomes of how students’ misbehaviors are addressed. With a commitment to reinstate students in community, rather than the historic practice of dismissing students from their school after misbehavior, the opportunity for learning continues—both in terms of behavioral expectations and academic content.”

For those like Bicondova, research empowers, serving to unravel issues and create solutions that will benefit students sitting in today’s classrooms. “It’s incredibly meaningful to be able to connect at-promise students with the resources they need,” said Bicondova, “and offer them that picture of hope that restorative practices provide.”